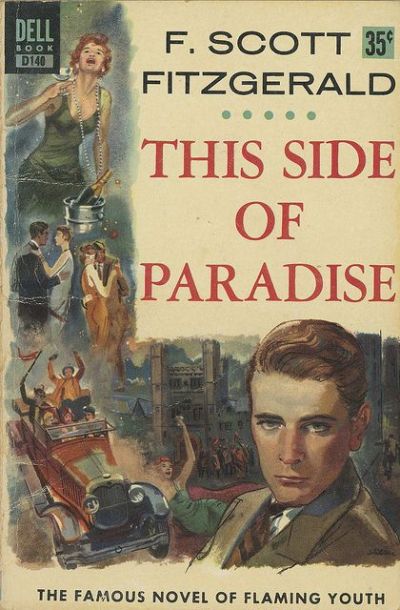

This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald - The Education of a Personage, The Supercilious Sacrifice

Previous - Book Two, Chapter III

Book Two - The Education of a Personage, Chapter IV - The Supercilious Sacrifice

Atlantic City. Amory paced the board walk at day’s end, lulled by the

everlasting surge of changing waves, smelling the half-mournful odor of the salt

breeze. The sea, he thought, had treasured its memories deeper than the

faithless land. It seemed still to whisper of Norse galleys ploughing the water

world under raven-figured flags, of the British dreadnoughts, gray bulwarks of

civilization steaming up through the fog of one dark July into the North Sea.

“Well—Amory Blaine!”

Amory looked down into the street below. A low racing car had drawn to a stop

and a familiar cheerful face protruded from the driver’s seat.

“Come on down, goopher!” cried Alec.

Amory called a greeting and descending a flight of wooden steps approached the

car. He and Alec had been meeting intermittently, but the barrier of Rosalind

lay always between them. He was sorry for this; he hated to lose Alec.

“Mr. Blaine, this is Miss Waterson, Miss Wayne, and Mr. Tully.”

“How d’y do?”

“Amory,” said Alec exuberantly, “if you’ll jump in we’ll take you to some

secluded nook and give you a wee jolt of Bourbon.”

Amory considered.

“That’s an idea.”

“Step in—move over, Jill, and Amory will smile very handsomely at you.”

Amory squeezed into the back seat beside a gaudy, vermilion-lipped blonde.

“Hello, Doug Fairbanks,” she said flippantly. “Walking for exercise or hunting

for company?”

“I was counting the waves,” replied Amory gravely. “I’m going in for

statistics.”

“Don’t kid me, Doug.”

When they reached an unfrequented side street Alec stopped the car among deep

shadows.

“What you doing down here these cold days, Amory?” he demanded, as he produced a

quart of Bourbon from under the fur rug.

Amory avoided the question. Indeed, he had had no definite reason for coming to

the coast.

“Do you remember that party of ours, sophomore year?” he asked instead.

“Do I? When we slept in the pavilions up in Asbury Park—”

“Lord, Alec! It’s hard to think that Jesse and Dick and Kerry are all three

dead.”

Alec shivered.

“Don’t talk about it. These dreary fall days depress me enough.”

Jill seemed to agree.

“Doug here is sorta gloomy anyways,” she commented. “Tell him to drink deep—it’s

good and scarce these days.”

“What I really want to ask you, Amory, is where you are—”

“Why, New York, I suppose—”

“I mean to-night, because if you haven’t got a room yet you’d better help me

out.”

“Glad to.”

“You see, Tully and I have two rooms with bath between at the Ranier, and he’s

got to go back to New York. I don’t want to have to move. Question is, will you

occupy one of the rooms?”

Amory was willing, if he could get in right away.

“You’ll find the key in the office; the rooms are in my name.”

Declining further locomotion or further stimulation, Amory left the car and

sauntered back along the board walk to the hotel.

He was in an eddy again, a deep, lethargic gulf, without desire to work or

write, love or dissipate. For the first time in his life he rather longed for

death to roll over his generation, obliterating their petty fevers and struggles

and exultations. His youth seemed never so vanished as now in the contrast

between the utter loneliness of this visit and that riotous, joyful party of

four years before. Things that had been the merest commonplaces of his life

then, deep sleep, the sense of beauty around him, all desire, had flown away and

the gaps they left were filled only with the great listlessness of his

disillusion.

“To hold a man a woman has to appeal to the worst in him.” This sentence was the

thesis of most of his bad nights, of which he felt this was to be one. His mind

had already started to play variations on the subject. Tireless passion, fierce

jealousy, longing to possess and crush—these alone were left of all his love for

Rosalind; these remained to him as payment for the loss of his youth—bitter

calomel under the thin sugar of love’s exaltation.

In his room he undressed and wrapping himself in blankets to keep out the chill

October air drowsed in an armchair by the open window.

He remembered a poem he had read months before:

“Oh staunch old heart who toiled so long for me,

I waste my years sailing along the sea—”

Yet he had no sense of waste, no sense of the present hope that waste implied.

He felt that life had rejected him.

“Rosalind! Rosalind!” He poured the words softly into the half-darkness until

she seemed to permeate the room; the wet salt breeze filled his hair with

moisture, the rim of a moon seared the sky and made the curtains dim and

ghostly. He fell asleep.

When he awoke it was very late and quiet. The blanket had slipped partly off his

shoulders and he touched his skin to find it damp and cold.

Then he became aware of a tense whispering not ten feet away.

He became rigid.

“Don’t make a sound!” It was Alec’s voice. “Jill—do you hear me?”

“Yes—” breathed very low, very frightened. They were in the bathroom.

Then his ears caught a louder sound from somewhere along the corridor outside.

It was a mumbling of men’s voices and a repeated muffled rapping. Amory threw

off the blankets and moved close to the bathroom door.

“My God!” came the girl’s voice again. “You’ll have to let them in.”

“Sh!”

Suddenly a steady, insistent knocking began at Amory’s hall door and

simultaneously out of the bathroom came Alec, followed by the vermilion-lipped

girl. They were both clad in pajamas.

“Amory!” an anxious whisper.

“What’s the trouble?”

“It’s house detectives. My God, Amory—they’re just looking for a test-case—”

“Well, better let them in.”

“You don’t understand. They can get me under the Mann Act.”

The girl followed him slowly, a rather miserable, pathetic figure in the

darkness.

Amory tried to plan quickly.

“You make a racket and let them in your room,” he suggested anxiously, “and I’ll

get her out by this door.”

“They’re here too, though. They’ll watch this door.”

“Can’t you give a wrong name?”

“No chance. I registered under my own name; besides, they’d trail the auto

license number.”

“Say you’re married.”

“Jill says one of the house detectives knows her.”

The girl had stolen to the bed and tumbled upon it; lay there listening

wretchedly to the knocking which had grown gradually to a pounding. Then came a

man’s voice, angry and imperative:

“Open up or we’ll break the door in!”

In the silence when this voice ceased Amory realized that there were other

things in the room besides people... over and around the figure crouched on the

bed there hung an aura, gossamer as a moonbeam, tainted as stale, weak wine, yet

a horror, diffusively brooding already over the three of them... and over by the

window among the stirring curtains stood something else, featureless and

indistinguishable, yet strangely familiar.... Simultaneously two great cases

presented themselves side by side to Amory; all that took place in his mind,

then, occupied in actual time less than ten seconds.

The first fact that flashed radiantly on his comprehension was the great

impersonality of sacrifice—he perceived that what we call love and hate, reward

and punishment, had no more to do with it than the date of the month. He quickly

recapitulated the story of a sacrifice he had heard of in college: a man had

cheated in an examination; his roommate in a gust of sentiment had taken the

entire blame—due to the shame of it the innocent one’s entire future seemed

shrouded in regret and failure, capped by the ingratitude of the real culprit.

He had finally taken his own life—years afterward the facts had come out. At the

time the story had both puzzled and worried Amory. Now he realized the truth;

that sacrifice was no purchase of freedom. It was like a great elective office,

it was like an inheritance of power—to certain people at certain times an

essential luxury, carrying with it not a guarantee but a responsibility, not a

security but an infinite risk. Its very momentum might drag him down to ruin—the

passing of the emotional wave that made it possible might leave the one who made

it high and dry forever on an island of despair.

... Amory knew that afterward Alec would secretly hate him for having done so

much for him....

... All this was flung before Amory like an opened scroll, while ulterior to him

and speculating upon him were those two breathless, listening forces: the

gossamer aura that hung over and about the girl and that familiar thing by the

window.

Sacrifice by its very nature was arrogant and impersonal; sacrifice should be

eternally supercilious.

Weep not for me but for thy children.

That—thought Amory—would be somehow the way God would talk to me.

Amory felt a sudden surge of joy and then like a face in a motion-picture the

aura over the bed faded out; the dynamic shadow by the window, that was as near

as he could name it, remained for the fraction of a moment and then the breeze

seemed to lift it swiftly out of the room. He clinched his hands in quick

ecstatic excitement... the ten seconds were up....

“Do what I say, Alec—do what I say. Do you understand?”

Alec looked at him dumbly—his face a tableau of anguish.

“You have a family,” continued Amory slowly. “You have a family and it’s

important that you should get out of this. Do you hear me?” He repeated clearly

what he had said. “Do you hear me?”

“I hear you.” The voice was curiously strained, the eyes never for a second left

Amory’s.

“Alec, you’re going to lie down here. If any one comes in you act drunk. You do

what I say—if you don’t I’ll probably kill you.”

There was another moment while they stared at each other. Then Amory went

briskly to the bureau and, taking his pocket-book, beckoned peremptorily to the

girl. He heard one word from Alec that sounded like “penitentiary,” then he and

Jill were in the bathroom with the door bolted behind them.

“You’re here with me,” he said sternly. “You’ve been with me all evening.”

She nodded, gave a little half cry.

In a second he had the door of the other room open and three men entered. There

was an immediate flood of electric light and he stood there blinking.

“You’ve been playing a little too dangerous a game, young man!”

Amory laughed.

“Well?”

The leader of the trio nodded authoritatively at a burly man in a check suit.

“All right, Olson.”

“I got you, Mr. O’May,” said Olson, nodding. The other two took a curious glance

at their quarry and then withdrew, closing the door angrily behind them.

The burly man regarded Amory contemptuously.

“Didn’t you ever hear of the Mann Act? Coming down here with her,” he indicated

the girl with his thumb, “with a New York license on your car—to a hotel like

this.” He shook his head implying that he had struggled over Amory but now gave

him up.

“Well,” said Amory rather impatiently, “what do you want us to do?”

“Get dressed, quick—and tell your friend not to make such a racket.” Jill was

sobbing noisily on the bed, but at these words she subsided sulkily and,

gathering up her clothes, retired to the bathroom. As Amory slipped into Alec’s

B. V. D.’s he found that his attitude toward the situation was agreeably

humorous. The aggrieved virtue of the burly man made him want to laugh.

“Anybody else here?” demanded Olson, trying to look keen and ferret-like.

“Fellow who had the rooms,” said Amory carelessly. “He’s drunk as an owl,

though. Been in there asleep since six o’clock.”

“I’ll take a look at him presently.”

“How did you find out?” asked Amory curiously.

“Night clerk saw you go up-stairs with this woman.”

Amory nodded; Jill reappeared from the bathroom, completely if rather untidily

arrayed.

“Now then,” began Olson, producing a note-book, “I want your real names—no damn

John Smith or Mary Brown.”

“Wait a minute,” said Amory quietly. “Just drop that big-bully stuff. We merely

got caught, that’s all.”

Olson glared at him.

“Name?” he snapped.

Amory gave his name and New York address.

“And the lady?”

“Miss Jill—”

“Say,” cried Olson indignantly, “just ease up on the nursery rhymes. What’s your

name? Sarah Murphy? Minnie Jackson?”

“Oh, my God!” cried the girl cupping her tear-stained face in her hands. “I

don’t want my mother to know. I don’t want my mother to know.”

“Come on now!”

“Shut up!” cried Amory at Olson.

An instant’s pause.

“Stella Robbins,” she faltered finally. “General Delivery, Rugway, New

Hampshire.”

Olson snapped his note-book shut and looked at them very ponderously.

“By rights the hotel could turn the evidence over to the police and you’d go to

penitentiary, you would, for bringin’ a girl from one State to ’nother f’r

immoral purp’ses—” He paused to let the majesty of his words sink in. “But—the

hotel is going to let you off.”

“It doesn’t want to get in the papers,” cried Jill fiercely. “Let us off! Huh!”

A great lightness surrounded Amory. He realized that he was safe and only then

did he appreciate the full enormity of what he might have incurred.

“However,” continued Olson, “there’s a protective association among the hotels.

There’s been too much of this stuff, and we got a ’rangement with the newspapers

so that you get a little free publicity. Not the name of the hotel, but just a

line sayin’ that you had a little trouble in ’lantic City. See?”

“I see.”

“You’re gettin’ off light—damn light—but—”

“Come on,” said Amory briskly. “Let’s get out of here. We don’t need a

valedictory.”

Olson walked through the bathroom and took a cursory glance at Alec’s still

form. Then he extinguished the lights and motioned them to follow him. As they

walked into the elevator Amory considered a piece of bravado—yielded finally. He

reached out and tapped Olson on the arm.

“Would you mind taking off your hat? There’s a lady in the elevator.”

Olson’s hat came off slowly. There was a rather embarrassing two minutes under

the lights of the lobby while the night clerk and a few belated guests stared at

them curiously; the loudly dressed girl with bent head, the handsome young man

with his chin several points aloft; the inference was quite obvious. Then the

chill outdoors—where the salt air was fresher and keener still with the first

hints of morning.

“You can get one of those taxis and beat it,” said Olson, pointing to the

blurred outline of two machines whose drivers were presumably asleep inside.

“Good-by,” said Olson. He reached in his pocket suggestively, but Amory snorted,

and, taking the girl’s arm, turned away.

“Where did you tell the driver to go?” she asked as they whirled along the dim

street.

“The station.”

“If that guy writes my mother—”

“He won’t. Nobody’ll ever know about this—except our friends and enemies.”

Dawn was breaking over the sea.

“It’s getting blue,” she said.

“It does very well,” agreed Amory critically, and then as an after-thought:

“It’s almost breakfast-time—do you want something to eat?”

“Food—” she said with a cheerful laugh. “Food is what queered the party. We

ordered a big supper to be sent up to the room about two o’clock. Alec didn’t

give the waiter a tip, so I guess the little bastard snitched.”

Jill’s low spirits seemed to have gone faster than the scattering night. “Let me

tell you,” she said emphatically, “when you want to stage that sorta party stay

away from liquor, and when you want to get tight stay away from bedrooms.”

“I’ll remember.”

He tapped suddenly at the glass and they drew up at the door of an all-night

restaurant.

“Is Alec a great friend of yours?” asked Jill as they perched themselves on high

stools inside, and set their elbows on the dingy counter.

“He used to be. He probably won’t want to be any more—and never understand why.”

“It was sorta crazy you takin’ all that blame. Is he pretty important? Kinda

more important than you are?”

Amory laughed.

“That remains to be seen,” he answered. “That’s the question.”

THE COLLAPSE OF SEVERAL PILLARS

Two days later back in New York Amory found in a newspaper what he had been

searching for—a dozen lines which announced to whom it might concern that Mr.

Amory Blaine, who “gave his address” as, etc., had been requested to leave his

hotel in Atlantic City because of entertaining in his room a lady not his wife.

Then he started, and his fingers trembled, for directly above was a longer

paragraph of which the first words were:

“Mr. and Mrs. Leland R. Connage are announcing the engagement of their daughter,

Rosalind, to Mr. J. Dawson Ryder, of Hartford, Connecticut—”

He dropped the paper and lay down on his bed with a frightened, sinking

sensation in the pit of his stomach. She was gone, definitely, finally gone.

Until now he had half unconsciously cherished the hope deep in his heart that

some day she would need him and send for him, cry that it had been a mistake,

that her heart ached only for the pain she had caused him. Never again could he

find even the sombre luxury of wanting her—not this Rosalind, harder, older—nor

any beaten, broken woman that his imagination brought to the door of his

forties—Amory had wanted her youth, the fresh radiance of her mind and body, the

stuff that she was selling now once and for all. So far as he was concerned,

young Rosalind was dead.

A day later came a crisp, terse letter from Mr. Barton in Chicago, which

informed him that as three more street-car companies had gone into the hands of

receivers he could expect for the present no further remittances. Last of all,

on a dazed Sunday night, a telegram told him of Monsignor Darcy’s sudden death

in Philadelphia five days before.

He knew then what it was that he had perceived among the curtains of the room in

Atlantic City.

The next - Book 2 Chapter V

Back to Fitzgerald's Book List